It’s evident as Douglas moves through the western American wilderness accompanied by surgeons, French Canadian traders, and Native American guides that he is a man possessing both a zeal for the new plants and animals he seeks as well as a friendly appeal to a wide array of people that join in his company along the way.

Here is a great piece of character illustration from Nesbit as Douglas returns from one of his demanding collection forays:

“As the bedraggled collector strolled across the low plain between the river and Fort Vancouver on August 30, observers thought that the shoeless man approaching the post, dressed in deerskin trousers and a battered straw hat, must be the lone survivor of a boat mishap on the river. After recognizing their resident naturalist, whose, “careworn visage had some appearance of escaping from the gates of death,” they were greatly relieved” (Nisbet, 115).

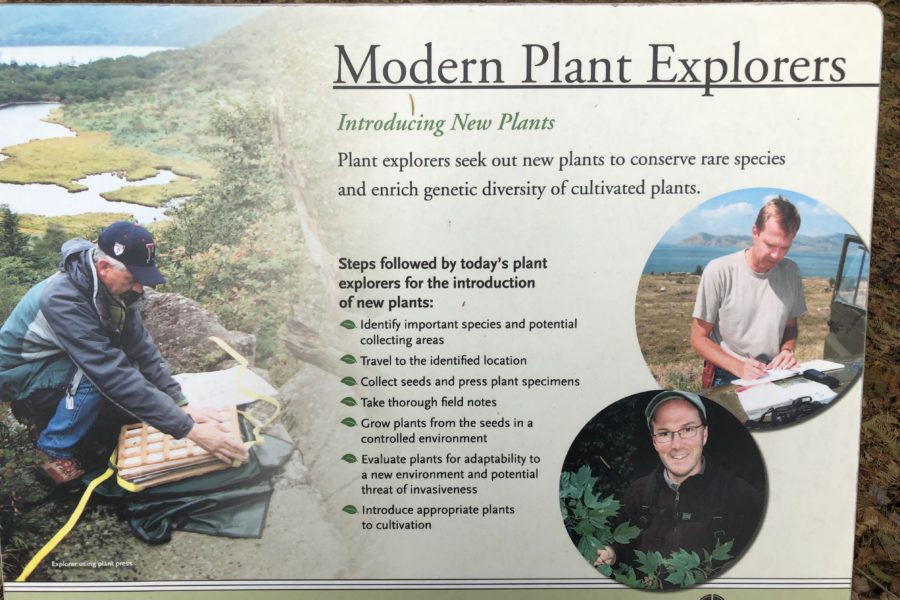

Douglas worked hard and with great fervor collecting plant specimens for the gardens at Chiswick, traveling thousands of miles in wild country in the name of science. After all, the great and honorable Douglas Fir is named for him; and the gigantic cones and sugary pitch of the sugar pine were other gems that captured his fancy during his mountainous jaunts. Although the plants were common to the Native American tribes and other frontier people that used them medicinally or as a part of their diet or otherwise, Douglas’ botanizing was to fortify these discoveries for Britain and bring home specimens that might thrive in the ornamental gardens, eventually leading to commercial stock. Discovering these plants and animals through the context of Douglas life, we see a blending of life, politics and culture unfolding before us. Douglas is a wild, determined character that bridges the gap in time between Lewis and Clark and Darwin.

The life of the collector leaves me with the powerful notion of metaphor: that in many ways all of our lives are collections in a way. One great resume, one giant portfolio.

Although not the gardens at Chiswick, we recently visited the coveted Morris Arboretum in Philadelphia, PA. Their Dawn Redwood collection is another testament to the lucrative process of exploration and plant discovery. Chinese botanists uncovered a secret cove of trees in 1946 that were thought to be extinct for many millions of years. Standing before these trees that came from seeds originally from the Arnold Arboretum of Boston, I felt myself travel through time. Thirty million years ago, I very well could have been standing before them at that exact location, discovering them again for the first time.

“There is something even in the lapse of time by which time recovers itself.”

-Henry David Thoreau

Maintenance practices like coronet cuts and large deadwood decaying over the critical root zone of some specimens alerted me to the importance of exploring maintenance practices that work, not just for individuals but for the entire ecological system as a whole. How can we make plants and their surrounding ecosystems healthier through our tree care routines? Looking closer at carbon sequestration, our maintenance footprint and what’s acceptable from an aesthetic perspective, we can explore not just the world around us but also our professional practices in that world. The Morris Arboretum collection inspires me even further to explore my arboriculture practices, most importantly mechanical maintenance procedures like pruning, mulching and planting practices. Even in a garden that has thrived so well for so long and with some much influential history, there are new things to see every day. What great testament! This is the bold and daring dynamic of nature and of botany-the depths of our inquiry does not limit it’s beautiful architecture.

Thoreau reminds us again that ” the greater part of the phenomena of Nature are…concealed from us all our lives. There is just as much beauty visible to us in the landscape as we are prepared to appreciate, not a grain more…man is only willing to see what concerns him.”

These things that we collect our whole lives: plants, ideas, experiences, lessons, jobs, clients, etc.; they are the substance by which we measure everything. We compare these things with others, and through this combination of sharing experiences we are inspired to search and explore even further. It’s no surprise that young David Douglas grew up reading Robinson Crusoe and Sinbad the Sailor, “from an early age, natural history consumed his interest, with his favorite occupations being fishing, picking wildflowers, collecting birds’ nests and capturing live birds,” (Nisbet, 4). David Douglas-The Collector- is a good reminder that we are all born explorers meant for a life of adventure. And whether it be in the ornamental landscape or wilderness or swinging through the trees, a collection of anything is really about the adventure in acquiring it; about the innate craving to discover things for the first time ourselves, and wonder even more.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.