A recent Black Walnut removal project has captured my fancy. Black Walnut, or Juglans nigra, is an esteemed tree for many reasons. The most popular probably being it’s spectacular wood grain and workability in the shop. Interestingly enough, the grain was not always appreciated in the light it is now, namely because of how the tree has grown in it’s natural range over time. As far as ecosystem benefits, it is a double edged sword. As a nut tree, it is fantastic for wildlife; in fact all nut lovers, be they flesh or fur. It’s nuts for the non-nut lover are a curse, leaving messy stains and sometimes a bad taste in a neighbors mouth every fall after cleaning up the blackened, staining, stinking fruit. It’s alleopathic qualities can have deadly affects on other plants growing within its reach. It’s large, compound leaves clog gutters, rake-heads and the inhibition to find any admiration in their amazing photosynthetic capabilities. For the arborist, or more specifically, for the climber of trees, or more appropriately, the accessor of crowns, the walnut is a joy. It’s strong branches, open form and wide crotch unions create work positioning opportunities for kings, queens and jesters alike. Black Walnut is a dichotomy like no other-royalty in the court of the urban forest, and a royal pain in the ass.

In Donald Culross Peattie’s chapter of A Natural History of North American Trees dedicated to Black Walnut, he tells us that, “there is significant difference between the solid Walnut furniture of the pioneers and the modern Walnut veneers. The old trees were mostly forest grown, hence slow growing; it took about a hundred years to produce Walnut of timber size under those conditions, and the boards show a straight grain and a very dark heartwood. Thus the old-time Walnut furniture often has a somber, heavy look, lacking refinement either in grain or design. But there is an honesty about it that links us to our past…The wood of the dooryard trees that are being cut now is quite other. It is lighter in color and much more varied and handsome in grain. This beauty can be brought out by skillful cutting…This method also permits the nicest matching of mirror-image cuts of the same fancy grain, resulting in butterfly or even double-butterfly or diamond patterns that no art of man can touch for delicate intricacy and subtle shading. They simulate, too, feathers, flames, or bees’ wings. In some cases the wood actually changes color, like changeable silk, when viewed and lighted first from one angle, then another, so that this once living stuff seems to keep still a secret life of its own” (Peattie, 169).

So then the lives of trees do change over time. Together there is a denseness and darkness in the grain. But alone, uniquely alone, produces a woodgrain, or a life-story rather, particularly different. Lighter, and more airy. Not an oral history, but a visual one, which, for trees, is an extremely unique characteristic compared to most living things. Dendrology if ever there was.

Speaking of other lives, the wonderful woman I happened to be working for said that her mother must have planted these trees.

“She probably didn’t know how big they would get,” she exclaimed. “And the squirrels love them!”

The property was situated in a nice section of town, and in the little residential complex my client owned there were a few rental units in a house at the back of the property, the main house, and next door, a recently sold mom-and-pop grocery store now turned house and pizza parlor. Her father ran the grocery store for years by selling high-quality meats, as the three walnut trees grew young and innocent, stout in twig and chambered in pith. Each, deep furrowed crevice in the maturing bark could have very well been cleaved as if from a butcher’s block.

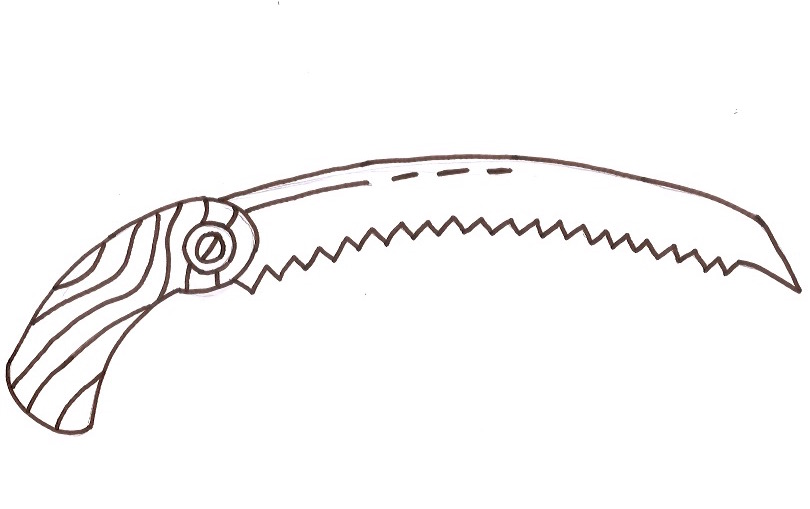

They were planted right along the property line in the back yard, along which now ran a chainlink fence that was a target for the entire removal project, as well as a shed and some knickknacks that had collected along the fence over the years. I am not a woodworker by any means, but one thing I did notice as I was setting up my face cuts and back cuts throughout the disassembly process was how pleasant the wood was to cut. And, after each top would blow out onto the rigging under the cackle of hinge wood breaking, and the stem wobbled under the action of moment, I would look down at the little cross-section before me and see the brilliant little swirls of heartwood squirming before my eyes. It was the open grown form of grain that Peattie writes of, “the wood of the dooryard trees.” And right there forty feet above the dooryard, each cut got better and better. And now that we just had a warm spell with freezing nights, the sap was flowing free from the large collars, one white strip around a dark heart of dead cells. Literally, time standing still.

For some reason time has moved slower on the Walnut job. We ordered pizza and hoagies from the little place next door and sat on the fallen spar of the first walnut that was felled nearest the main house. At twenty two inches it made the perfect seat, un-planed, un-sanded, un-level. An angry squirrel darted across the lawn and blasted up into the last two trees that we were currently taking a lunch break from, maybe to grab some final belongings I guess. The weather was just beautiful, unseasonably warm and pleasant. We had a bathroom and porch at our disposal in one of the empty rental units, coffee always on the brew, the neighbors were enjoying the progress of the job, the old guy in the back alley was very impressed (he said so himself), and the pizza and the hoagie hit the spot. Even if the rigging was slow and meticulous, who really gives a shit. We had it made.

“My mom always wanted to get rid of these trees once they got too big,” the homeowner revealed. “She’s probably so happy and sent this great weather!”

For the Black Walnut project is a great reminder of how many lives a tree does touch. These trees live on in all of us-in one way or another-in the trees we climb, the leaves we rake, the things and memories we make. These Walnut trees were a beautiful breed, I must say. But I could not sell the preservation treatment, although pressed I was to try, it was to no avail. Whatever I can do to get the work, for I am grateful for it and the memories that working in trees provides me. For trees are just that: memories made from time. Some are better than others. Sometimes we can preserve them, and sometimes they escape us, or the lessons they teach, as difficult in thought or process as that may be.

Well let me tell you, on the third day of this project the lofty feelings did not prevail. A crazy Nor’easter whipped up and brought heavy snows and wicked winds on top of a wet, thawing February ground-the deep, nutrient rich hillside soil that Black Walnut trees so dearly love. With a dump-trailer full and heavy with the beautiful and cursed wood, I spun my tires uphill into my lot and sunk, truck-bumper-and-trailer-tongue deep into the cold, muddy mire trying to turn the rig around. As I unloaded the trailer by hand and dug out the rig, I called a good friend to come pop me out of the hole I had spun myself into; and I realized that I was already way over on hours for the job, still had at least four loads of wood to pull out, and I didn’t make cabinets or book-matched veneers.

Nevertheless, time seemed to be standing still. And there is plenty of value and honesty in that.

2 Comments

Leave your reply.