We’ve all heard that famous credo arboriculture is both an art and a science. For this discussion I’d like to focus on the former object of that clause, the art. Although it may inevitably lead to the latter.

Robert Henri wrote in his classic work The Art Spirit, “A good painting is a remarkable feat of organization. Every part of it is wonderful in itself because it seems so alive in its share in the making of the unity of the whole, and the whole is so definitely one thing. You can look at a painting in but one way. That is, the way it is made. Whether you will or not you must follow its sequences,” (25).

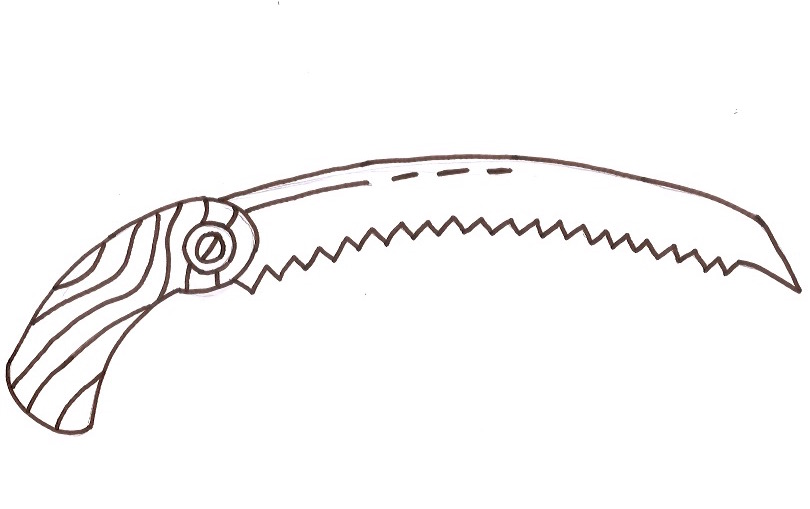

You must follow its sequences… In this way Henri shows us that art is an interpretation of structure. Although we may, in one sense, think of an individual tree as a work of art already, maybe it is a canvas on which we create something else. A deciphering. But what is it that we are creating? A subordinated limb, a cable, a brace; or simply the route or the motion through which we rope a piece out down through the great maze of the crown. The tree for the arborist is then, too, a medium. Every part of it is wonderful in itself…

I’ll never forget something Tony Tresselt taught me in one of his classes many years ago: that we should “take trees apart the way they are put together.” That sentiment has always stuck with me, and in this context I think it compliments quite nicely what Henri points to about what makes a good painting. Putting things together and taking them apart both require a mastery of organization. A vision of sequence. A great respect for creation.

Although we may take it for granted, a great arborist, much like a great artist, is a master in the pursuit of organization. Not only in the sense of tools and scheduling, but in the way we perceive our subject and our craft. Often times the first thing we look at is structure. In that structure is where we find that unique character of each individual tree. And especially the climbing arborist. How is the tree is put together? This is, above all else, what differentiates the unique character of all trees: their form. How they have individually grown in a massive and vast and different world is typically what intrigues us most about our subjects. We are wondering about which branch union can provide the best vantage for the work. For the rigging. And can it support the work that needs done. And most importantly, can it support itself? When the artist is gone, can the tree stand alone against the test of time? Perhaps these questions are too mighty for such a short talk.

Henri writes that “Art is the inevitable consequence of growth and is the manifestation of the principles of its origins,” (65). If Art is the inevitable consequence of growth, then so too is arboriculture. It is too great a similarity in this light. Through arboriculture, we can find ourself, our subject and our process. Our principles no doubt guide us at each cut, at each flip upward of the spliced end of our line. Because trees grow, so too does arboriculture grow.

The arborist can live in the trees we work, the arborist can live on in the trees we touch. We are like artists in that way.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.