A really wonderful book, The Long, Long Life of Trees by Fiona Stafford has me mesmerized. Stafford’s book is a natural history of sorts that explores how trees and human history have been beautifully intertwined; from symbolism in art to building infrastructure to souls passing on into the afterlife to religious symbols to holiday traditions to food and drink and medicine and cultural and national identities. Trees and what they mean to people have an incredibly long history.

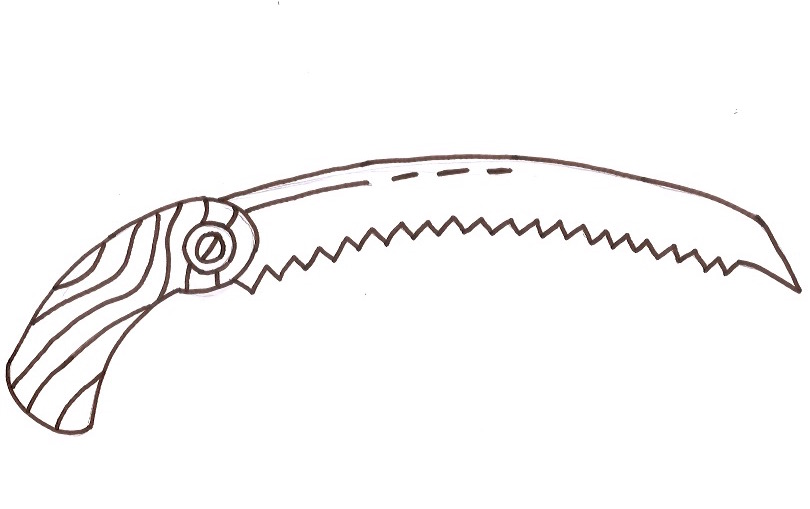

And so I’m thinking about the arborist, the actual history of making money off this relationship. I think of how ancient the trade must be. I mean, if we realistically consider the basics, that is: the tree and the blade, either one has remained pretty much the same for many thousand years. But typically my mind can only visually reach the black and white photographs of the early arborists from Davey and Bartlett with their flatbed or transplanting trucks busy at work, their climbers out on limbs in all the vintage fashion-manilla rope and blakes hitch and knickerbockers. But this trade is far, far more ancient than those popular images from the early 20th century.

Without any type of heavy research, I like to let my imagination run wild when I consider the ancient arborist. I imagine a cobbled hut tucked away in the farthest corner of a royal property. I’m not sure if it is England or Scotland or Italy or maybe even amongst the ancient Iranian alpine somewhere. Let’s just say 2,000 years ago (although I believe that to still be an infant examination of the craft). I imagine someone cleaning their saw with a concocted oil, thinking of tomorrow’s contract. Maybe it’s a large willow coppice or some yew pruning, or a cherry transplant, I’m not sure. Stafford does make mention of the Roman empire keeping their yews “firmly in line” (22). There must be some type of anxiety about the project though, whether is about time or resources, it’s only natural. Imagine the pressure of delivering on specs for The Emperor. I’d say that’s about as commercial as it gets as far as bidding goes. Nonetheless, the process of planning and preparing seems to me like it would be unfettered even in the depths of history. In the depths of my mind, I can feel the connection.

When I think of the elders, I always imagine countryside, sprawling estates if you will. In this instance, the modern arborist of the large, crowded cities doesn’t always match up. But consider, for a moment, the bustling and sunny culture of the ancient Mediterranean. Stafford takes us there. It’s a much more urban feel, like that of modern times. I can see the markets, crowded with people vending. The pride of the market is the olive, the fruit and the oil, which, as we know, can’t just be picked. It is a process. The olive tree needs care and nutrition and structure. And planting and harvesting. There is someone that provided that to the best olive trees and I imagine them busy in the mediterranean market pushing their olives after a heavy October harvest. Is this the ancient arborist too?

There is a murmur in the book as well of Noah’s arc being constructed of Cypress. Surely that must of been a low-impact harvesting situation. I’m wondering if they brought in climbers for felling the large trees as to save the stems from splitting apart. Or maybe that was favorable for the process? Taglines probably weren’t en vogue that far back, but I’m sure there were some people who were just a little faster and more accurate with the axe and with the saw. Those people are a critical part of the arboriculture lineage.

I’m finding that the farther back in history I go, the more you see the economy of trees: for their wood, for their fruit, for their chemicals, and then for their beauty and aesthetics. Stafford shines a brilliant light on this history. It’s fascinating to explore the relationship between trees and people. I think that’s where the arborist comes from. The arborist has always acted as the mediator in this relationship. They offered care to both trees and people. Neighborly disputes have existed as long as people have been neighbors. I can almost guarantee that there was an arborist out in the headgeline somewhere, cutting back just enough to please someone, and not just enough to keep someone else happy. The history of the arborist is as funny and as it is an economical thing to consider. I’m pretty honored to be a part of it.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.