Imagine with me the idea of truth, and how it applies to arboriculture. To find truth in arboriculture, we need to first look at the common definition. In order to formulate that definition, the question is asked: what is arboriculture; or rather, what is the essence of arboriculture? What is the arboriculture-ness of it all? The tree owner. The arborist. The tree. So then, it seems we are left with these three overlapping spheres. How those entities interact with one another, then, determines the essence of arboriculture.

A quick Google search yields this definition of arboriculture: “the cultivation of trees and shrubs.” The ISA’s study guide defines it this way: “arboriculture is both an art and a science. It combines skill and craft with knowledge and fact.” In other words, a more marketable version of “the cultivation of trees and shrubs.” Either way, we are left with an extremely vague boundary for exactly what arboriculture is. The essence remember, is what we’re after here. To pin down an exact truth about it. By definition though, we are floating on a sea of potential.

So, by merely reciting the definition, we get a cause, but no effect. For instance, you plant a tree, that’s arboriculture by definition. What about when someone doesn’t like it? The arborist must swoon in like a professor, like a mural painter or a sculptor, and explain just why the planted tree is so perfect and so right and so native. So then we see in this example that a vague definition works to include not only organic and biological elements, but also a human element. Which is quite good for business, mind you.

If we look to the word itself, the actual semantics, then maybe we find the essence there. Arbor, from the Latin arbor, literally means tree. And culture, also from the Latin cultus or cultura, meaning care. So, semantically, tree care. Perfect.

Care then, is a core idea in outlining the truth of arboriculture. Now we are getting somewhere. Care is so deeply embedded into us, so it makes sense that we would care for our trees as a civilization. Cultura. We prop them up and cable them back together when they are broken and plant new ones, give them medicine and lay dead ones to rest. Arboriculture is intertwined into our human and local culture like DNA braids, or sixteen-strand. “In trees we see ourselves,” says the historian Thomas J. Campanella, “we appreciate the symmetry of human and sylvan life. In the seasons of the tree we find a map of our own lives,” (from the introduction of Jill Jonnes Urban Forestry: A Natural History of Trees and People in the American Cityscape).

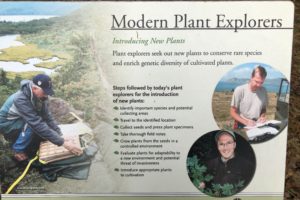

In an email correspondence with Ed Gilman some months ago he made mention that people’s perception of healthy pruning thresholds alone varies widely based on his observations from several hundred pruning workshops he’s done all over the world. So then, by this account, arboriculture is a reflection of the local culture in which it comes out of. There is not one truth, but many perceptions of it. So, does this mean that the essence of arboriculture is different everywhere? And for everyone? Maybe.

But not so fast. For dealing with this dilemma, now would be a good time to introduce the arborist. For we cannot define the essence of arboriculture without discussing the arborist. The worker and the helper of trees, or the remover of trees, or the planter of trees. The ancient tree caregiver. All these facades can suffice, some more pertinent than others given everyone’s particular area of expertise, though. So, even when we consider the arborist them self, we see that there are different roles in actually caring for trees. Root zone management. Plant health care. Climbing, rigging, pruning, installation and cabling and bracing. There are boundless areas of research into trees and technology and medicine and communicative abilities on microscopic levels. Nurseries and crane companies. So then, just who is the arborist?

I would like to turn for a moment to Martin Heidegger and a quotation from his preliminary considerations in his book The Essense of Truth, where he writes”In the Middle Ages and later the definition [of truth] was: veritas est adaequatio rei et intellectus site enuntiationis, truth is the bringing of the thought or proposition into alignment with the thing,” (Heidegger).

So then, according to this excerpt truth in arboriculture is aligning how we think about trees with the tree itself, right? Or, is it aligning how we think about trees with how people that own trees think about them? I feel like I’ve done that a time or two just for a buck. Or better yet, and far more accepted, is aligning how people think about trees that need tree care with how we, as arborists (intellectuals) think about trees. Either way, I like the incite that Heidegger provides because this definition speaks very much so to the truth of arboriculture. Here I think we get a good head start on the essence.

We are bringing the thought or proposition into alignment with the thing. So then, as the carer for trees the arborist is summoned by the tree owner to provide a service for the tree. Here again are the three spheres, resurfacing from earlier in the discussion. There is a proposition about the thing, the tree (sick, dead, etc.). Therefore, it is the arborist’s job to bring that proposition into alignment with that specific tree. Like focusing a microscope, or a telescope, or tuning a piano. Then the essence of the arborist, and of arboriculture, is to align these three spheres, into a perfect arbor eclipse.

Which may only happen once every seventy five million years.

2 Comments

Leave your reply.