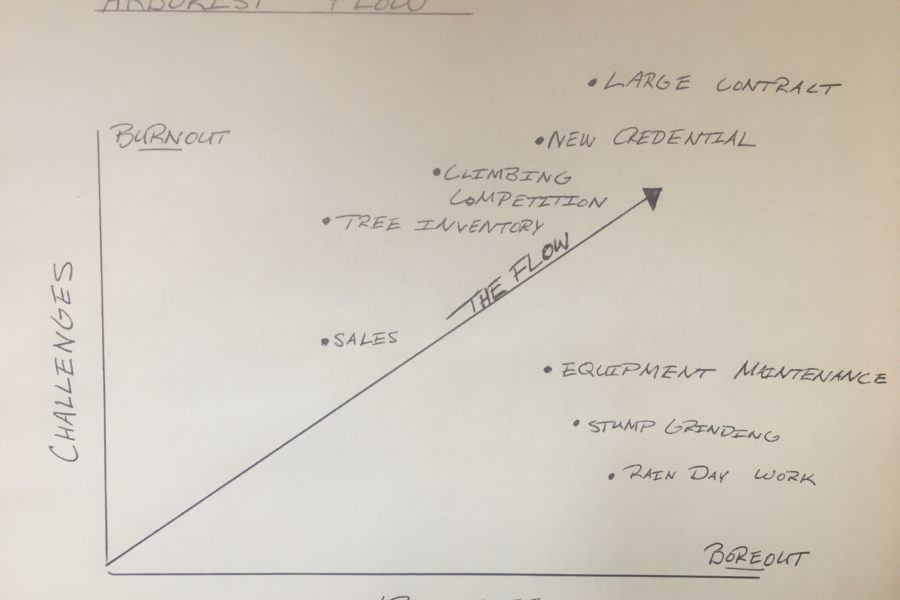

I’m currently reading The Decision Book: 50 Models for Strategic Thinking by Mikael Krogerus and Roman Tshappeler. As the title suggests, it is a compilation of popular models derived from different areas of research, economics and philosophy aimed at either self-improvement or general improvement applied to many types of operational systems. I came across one model in particular, called The Flow Model (47) which I think relates to arboriculture quite well.

“Over two thousand years ago, Aristotle came to the unsurprising conclusion that what a person wants above all is to be happy…In 1961 US psychologist Mihaly Csiksgentmihalyi wrote ‘While happiness itself is sought for its own sake, every other goal-health, beauty, money or power-is valued only because we expect that it will make us happy.’ He called it ‘flow’. But when are we ‘in the flow’?” (47).

To paraphrase, here’s what a thousand people had to say about what causes happiness, or flow (47):

- intense focus on something we get to choose

- neither under-challenging nor over-chellenging

- a clear objective with immediate feedback

“Csiksgentmihalyi discovered that people who are ‘in the flow’ not only feel a profound sense of satisfaction, they also lose track of time and forget themselves completely because they are so immersed in what they are doing. Musicians, athletes, actors, doctors and artists describe how they are happiest when they are absorbed in an often exhausting activity-totally contradicting the commonly held view that happiness has to do with relaxation,” (47).

For the arborist, we are often challenged with situations that make us uncomfortable either from a physical mental perspective. New challenges can make us uncomfortable. For instance: a large removal or a diagnosis project with the intent of preserving a highly valuable tree. These types of day-to-day challenges consume us. Some of us lose sleep thinking about the project’s commencement (tomorrow! the day after!) and almost every other thought is a potential key to unlocking the solution to solving that complex problem before us.

Challenges are different for everyone. Some of us truly enjoy a good rain day every now and again, so we can lay out a large mandala of gear, inventorying every prussic and carabiner, checking its action, drying ropes, cutting and taping frayed ends, cleaning handsaws and sharpening and tuning every power saw in the fleet. Others loathe these days, begging for the moment when the clouds will break and they can climb back up into the crown and get back to work, escaping the mundane strokes of the round file or the messy, grumbling hum of a stump grinder. As individuals, we thrive on different challenges, and every great team has different individuals that will rise to different occasions. At certain times, our teammates flow is what carries us through our ‘burnout’ or ‘boreout’ moments.

The flow hardly remains the same for the duration of our career. As we grow, what once was a challenge many years ago now becomes an easy task in the present because, hopefully, our abilities increase the longer we are exposed to challenges. Therefore, flow, or happiness, grows with our abilities. Many people choose to take advantage of that comfort in challenging situations and share it with others in the industry through teaching and training. In this sense, flow is a legacy that we pass on to others.

Dealing with simple challenges leads to the ability to deal with greater challenges. Wearing PPE, inspecting climbing and rigging ropes, discussing a pre-work plan, executing a pre-climb inspection, identifying common, species-specific biotic and abiotic disorders; all of these things seem simple but for many arborists, including myself, challenge our position of complacency and general field knowledge on a day-to-day basis. Even though we’ve learned the basic themes sometime in the past doesn’t necessarily mean we remember them. Challenges are a great way to revisit the basics, and incorporate those starting points into every problem solving process we embark on. Every challenge is an opportunity to re-learn the things we already know.

According to the model, by catching (or being consumed by) the flow, we are able to avoid being burned out or bored out. This is important because in either extreme, especially for the arborist, being burned out or bored out can lead to complacency and catastrophic failure. We move away from the flow, and therefore we inherently loose our critical, intense focus. In any task the arborist should choose to take on, by intensely focusing on a clear objective, we can better get lost in the process of the job before us.

Do what makes you flow and fly higher.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.