As I re-read David George Haskell’s work The Song of Trees, I admire his observations of trees, and the role that they play in the ethics and aesthetics of the networks that they affect. I’ve chosen three passages that struck a chord with me as they pertain to the urban forest, and working with trees as an arborist in general.

“But trees are masters of integration, connecting and unselfing their cells into the soil, the sky, and thousands of other species. Because they are not mobile, to thrive they must know their particular locus on Earth far better than any wandering animal. Trees are the Platos of biology. Through their Dialogues, they are the best-placed creatures of all to make aesthetic and ethical judgements about beauty and good in the world,” (Haskell, 153).

Ecosystem services abound, trees are a matrix of function, both within and without. They are constant givers, and simple contemplators in response to their surroundings and microclimates. To think about the immobility of a tree is fascinating, but that is quickly overshadowed by the tree’s dynamic capabilities as a provider for all forms of life. It is a false immobility in some senses. Trees are the master link in the circle of life, giving breath to the world, from one place to all places.

“Trees change the grammar of the street, allowing sentences that are otherwise silenced,” (209).

From a design perspective it is true. Psychologically, monetarily, and environmentally, healthy trees make the landscape and the people living within it healthier. Trees change the outline of the city, giving it a softer hue. Landscape design that uses trees as major elements can having lasting emotional affects. I think about the moving work of Michael Arad’s design of the World Trade Center Memorial, and the amazing effort that went into that project, and how deep and powerful of a story those trees tell.

“During the harvest, every tree became a center of human story-telling, stories that comprise people, trees, and the relationships among them. By the time workers have picked a field [of olive trees], tens of thousands of words have flown from mouth to ear. Part of the landscape’s mind-its memories, connections, rhythms-is thereby held in human consciousness. Work among the olive trees does more than yield oil; it creates and deepens the stories from which are made human and ecological communities,” (230).

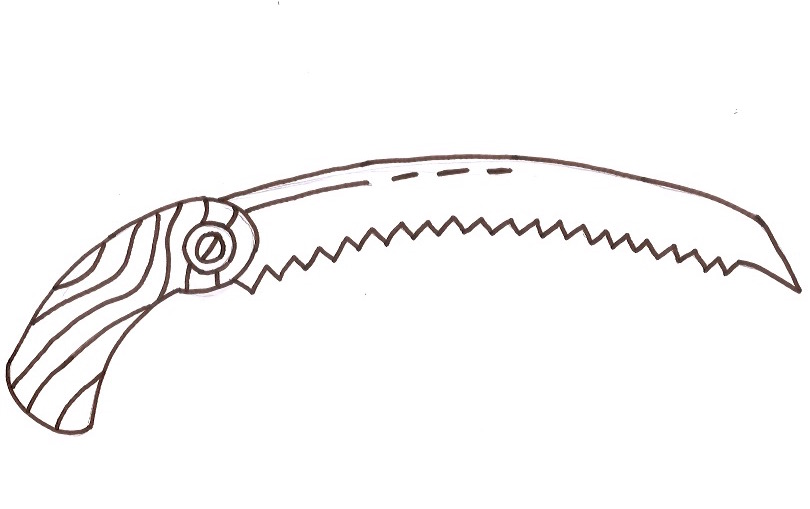

As a tree worker we become a part of the landscape fabric, and the human fabric too of the communities in which we work. Our story is a web of stories. Many times the trees are only a backdrop, sometimes momentarily unimportant compared to the other realities of life unfolding. As Shakespeare wrote, “All the world’s a stage, and the men and women merely players.” Well then trees can be likened to the omniscient narrator of nature, all-knowing and all-seeing. They can at times be a pain, no more than a paycheck, unimportant until it’s off the schedule, and on to the next one. But the true culture of working trees is made from the people that choose that same path overtime, by the people that cross it. Friends and mentors we work with are sometimes far more critical than any champion tree or high-paying contract. We find solace in our specific community of tradecraft. We find the importance of this tradition in the sacred bond that brings us to it.

Trees connect people in the most powerful ways.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.