Tree identification can provide many hours of winter fun, especially in a temperate regions when leaves drop and arborists are forced to observe auxiliary plant structures to aid in identification. We can learn many things about tree biology from the utility of tree identification that will have a direct impact in selling plant health care and educating clients. Specialized tree morphologies are many and unique, and the process of tree identification forces us to look at a smaller plant fragments for a clearer vision of trees as a whole.

The abscission zone is an especially interesting place for a number of different reasons. It is here where arborists can learn a lot about both deciduous tree biology as well as taxonomy and plant identification. According to the ISA Cerified Arborist Certification Study Guide, the abscission zone serves the physiological purpose of aiding leaf drop and also protecting the tree from desiccation and pathogen infection. It is a hot spot of special cells and growth regulators (The Guide, 5-6). The abscission zone is also a great place to look for identifying trees. We can observe several plant structures at abscission zones: buds (both type and arrangement on the stem), leaf scars and also twig characteristics (hairy, smooth, lenticel presence, etc.). These telling characteristics are a great way to identify trees that have already dropped their leaves, and we get to observe all of those characteristics at the abscission zone. The abscission zone tells an encompassing story of tree biology.

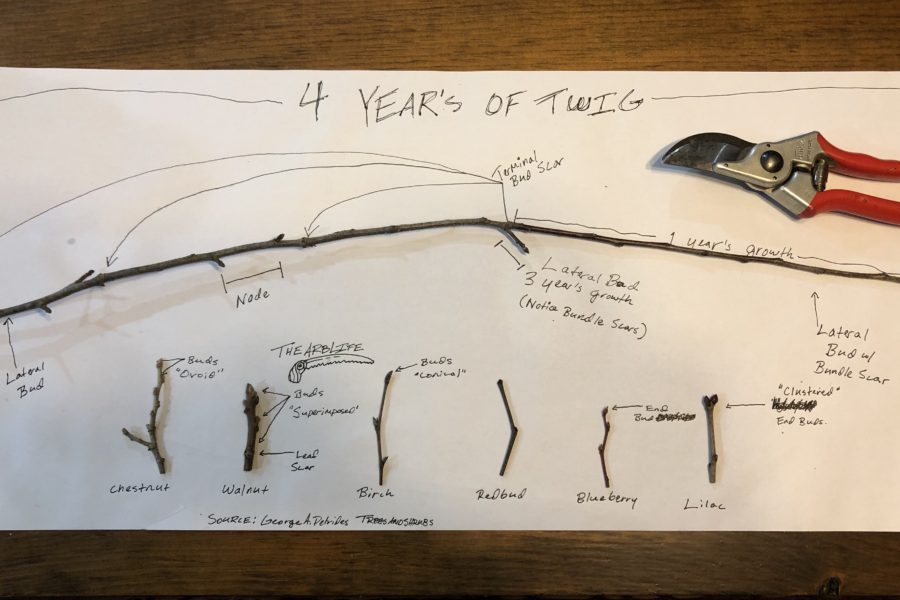

Bud seriously, how much can we learn from bud structure? First, let’s consider the vast monikers of bud structure, again from the ISA Study guide Figure 2-8: narrowly conical (beech), ovoid (chestnut), conical (chestnut oak), accessory (scrub oak), superimposed (walnut), one-scaled (willow), stalked (striped maple), outermost scale centered directly over leaf scar (aspen), scales in two ranks (elm), striate scales (hornbeam), rounded (white ash), valvate showing stipulate scar encircling twig (tulip tree). For each individual tree is a unique and telling bud. And let’s not forget about the other key feature at the abscission zone: the leaf scar. Here we are reminded of the beautifully unique arrangements of bundle scars and the truths of tree identity in which they speak. And just like the bundle scars underneath them, buds are also highly varied physically, which is how they can serve as a critical tool in tree identification.

The difference between terminal buds and lateral buds is their locations upon the stem; particularly these areas are known as nodes. Terminal buds, located at the apex or tip of the twig, can sometimes illustrate other unique qualities such as being clustered in bunches or pair with just one other like it. As if we were living in a Dr. Seuss story, we learn that end buds (another term for the terminal bud) can either be true or false. The Peterson Field Guide for Trees and Shrubs by George A. Petrides, for example tells us the American Hazelnut has false end buds, while European Black Alder’s are true. In both circumstances they are very real. In that same and trusted guide we see that Fire Cherry’s twig tips are crowded with buds, as well as oaks, whereas the Eastern Dwarf Cherry’s twig tips are not. Some Lilacs have just two. Bud scales are also a telling feature for tree identification purposes. Under the aid of a simple hand lens we can count bud scales. Acknowledging the Peterson Guide again, we can see that some buds are hairy and don’t have scales (American Snowbell) while some buds are bare and have exactly 2 scales (Persimmon). Unfortunately, Dr. Seuss did not write about the physical diversity of tree buds and how it pertains to taxonomy, although he may have enjoyed the task.

Identifying trees also provides the arborist with an excellent starting point for a conversation in tree health care. A small clip from the end of a branch twig provides us with a first hand opportunity to bring our clients into the classroom of tree biology. It’s a readily available physical aspect of the tree which we can explain, hands on, how the biological processes of trees work and what functions they serve. We can observe the length of the twig between terminal bud scars to make observations on yearly growth and vigor. If the topic moves to pruning, there is the potential to explain how removing these buds, will affect tree growth: photosynthetic capability, lateral growth activation (directional pruning), plant growth regulator (hormone) redirection and imbalance. There may be a few soft or hard scale present on the twig, or a few clusters of adelgid, or a twig gall, or twisted twigs damaged by herbicide, or something really cool that we’ve never seen before. The point is, grabbing a tree by it’s buds can provide hours of fun for the arborist in conversation with their clients. In this sense, simply looking to identify trees can lead us into the future of that tree’s management.

I know, I know: chlorophyll borophyll. Bud seriously, take into consideration the vast story we can read and recite by studying the buds of trees. From chemical compounds to unique birthmarks to the chronology of vigor; a bud is, literally, one of the great starting points for arborists and arboriculture. It is now magnified in winter, when the deciduous demand truly exists to look to buds for the answer to the questions: who, what, why, when, where and how.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.